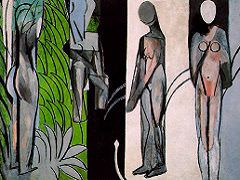

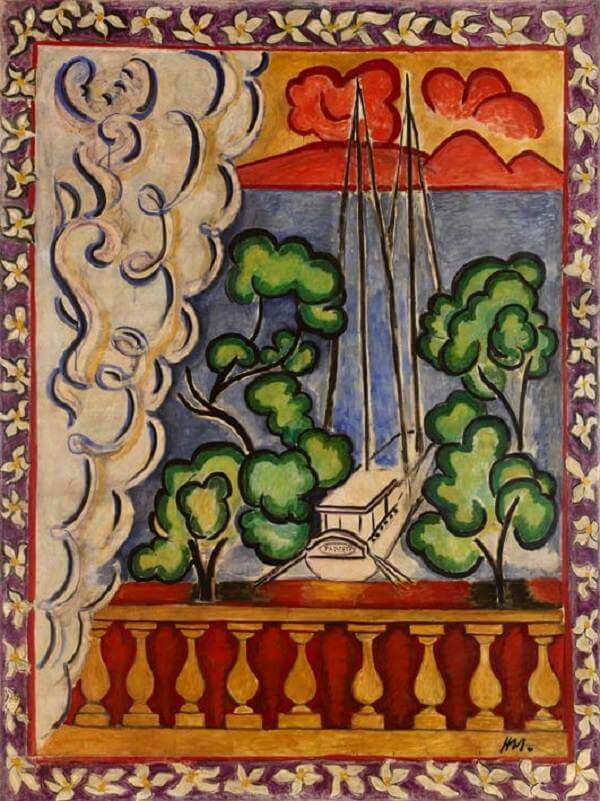

Window in Tahiti, 1935 by Henri Matisse

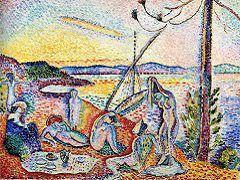

During his visit to the South Seas, specifically Tahiti, Matisse did several remarkable drawings but no paintings. This was in 1930, just before he began work on the Barnes Dance. Hence it was not until five years after the trip that the artist sought to condense his experiences, relying in part on studies realized on the spot, producing this tapestry cartoon which functions as a monumental souvenir of his voyage. It serves to conclude a major theme in his art that begins with the development of the refrain of Baudelaire's Invitation au voyage in Luxe, calme et volupte. The several voyages, real and artistic, have now been completed, and for the first time in Matisse's art we can detect a valedictory note. Carrying over from the earlier picture is only the ship, moored with its sails furled. As we look through the open window across this placid, tranquil scene, the somber colors suggest a new and different sort of light in his work. However, here the theme of the open window is almost completely sublimated into the motif of the decorative border. Only the balustrade at the bottom suggests an architectural reference for the point of view from which the artist is recording his sensations. He had employed this decorative frame as early as Still Life with Aubergines, and it was originally part of another large, tapestry-like painting of 1936, The Nymph in the Forest, a picture that may well be a pendant for the present design.

Unlike Le Luxe, here in Window in Tahiti the human figure has been banished, much as in the studio interiors of 1911. The foliage and clouds and the indications of a curtain on the left are of a curving pattern whose scale and weight is remarkably uniform throughout. One is reminded of certain of the Tangier landscapes of 1912, but now the design is firmer, more measured, more the result of reflection and meditation, whereas in the earlier tropical landscapes we are keenly aware of the artist trying to record, albeit in a stylized fashion, the immediacy of the scene before him. Much as with the Barnes version of Dance, Matisse has produced a composition summing up a continuity of experiences with the recurring motifs of his life's work. To a degree it is a less approachable painting than much that has gone before, but this Olympian attitude is understandable in the work of an artist now past his sixty-fifth birthday.