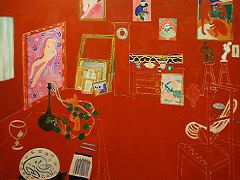

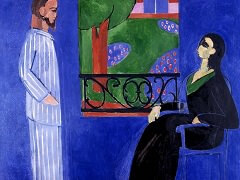

The Moroccans, 1912 by Henri Matisse

Matisse conceived The Moroccans with all the deliberation and patience of a nineteenth-century academic master preparing a machine for some future official Salon. From the same letter to Camoin in which we learn of his efforts of 1913 on Bathers by the River, we learn that the concept of a definitive effort summing up his North African experiences was in the forefront of Matisse's mind. And despite the fact that his somewhat disruptive encounter with Cubism was occupying him at this period and is in evidence here, this remains one of his most totally satisfying large-scale works. The picture's novel tripartite division seems to break all possible laws of compositional order, and yet for Matisse it works perfectly. It is as if he were deliberately setting himself an impossible task of achieving overall unity, and then proceeding to accomplish it with apparent yet deceptive ease. It would seem that the black ground separating the three distinct parts, and also working itself into various areas of them, is the basis of his success.

The architecture of the upper left evokes Entrance to the Kasbah, and the display of melons and their leaves on what would seem to be the pavement of a public market is suggestive of the limpid, lyrical designs of Moroccan Garden, painted on his first trip to Tangier. These elements are situated one above the other on the left side. On the right we find a group of Moroccans at prayer, and this is the most challenging, hard-to-read part of the composition - in contrast to the forthright decorative simplicity of the opposite side. However, their gestures of supplication are somehow clarified by the design of the several melons in the lower left. This area has been mistakenly identified as a group of figures touching their foreheads to the ground. The mistake is understandable because of the expressive abstractness of their design, and it seems quite within the realm of possibility that Matisse intended the ambiguity in order to clarify the more puzzling passages at the right. It is also a structural device that serves to link the otherwise fragmented composition, especially as the worshipers seem to be facing the melons and vice versa.

The final unifying device is the repetition of the circular motif throughout the three elements, so that the domes of the architecture, the blue flowers in the pot, the spherical melons, and the rounded bodies of the worshipers all share the same motif. In this picture Matisse provides us with a distillation of his sensations, summing up his North African experiences much as Dance and Music, concentrate all his efforts from Joy of Life on.