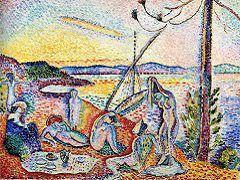

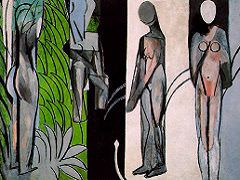

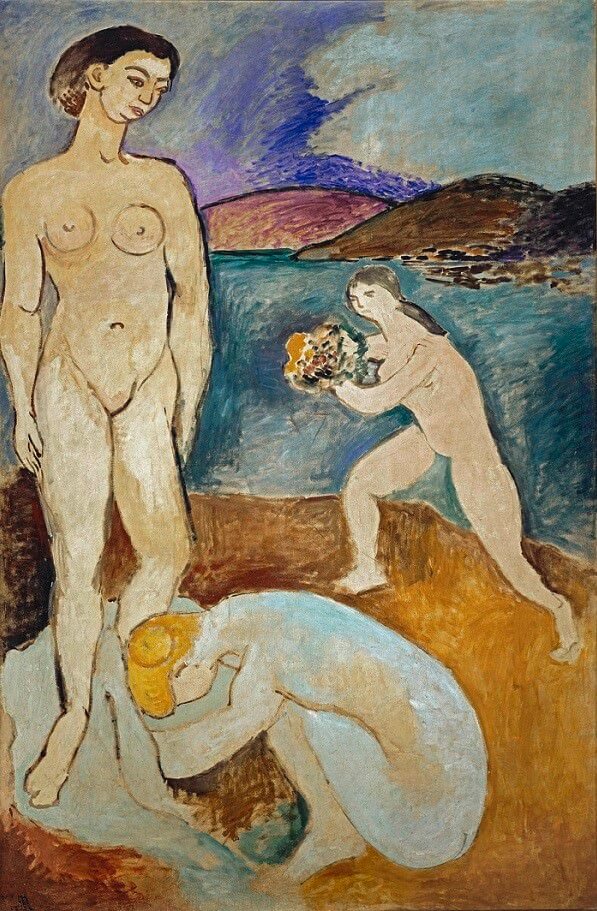

Le Luxe I, 1907 by Henri Matisse

Le Luxe I, a full-size study for the final version in Copenhagen, is undoubtedly more "interesting" to the critic preoccupied with the evolution of Matisse's art. However, it is infinitely less complete, less "realized" than the more articulate, simplified, and compact statement of Le Luxe II, which remains one of the artist's most serene images. Iconographically a condensation of Luxe, calme et volupte, its two major figures, the statuesque but hardly sculptural standing figure and the one crouching at her feet, actually derive from the two figures to the left of Joy of Life. The crouching figure has now been reversed, and the standing one here lowers her arms. The image of Lesbos, already present in Matisse's Neo-Impressionist composition and even in Joy of Life, is here made more explicit with the gesture of the bouquet-bearing figure hurrying in from the right. Indeed, Matisse would develop this concept further in the small Music, with the embracing couple, both female, dancing to the music of the solitary male violinist. Parallel themes reappear in numerous drawings and a few paintings of paired odalisques dating from the 1920s and 1930s. Here, in Le Luxe, Baudelaire's verses, especially "La, tout n'est qu'ordre et beaute," seem more fully realized than before, with the repetition of the theme of a world in which the male figure, with all its implications, is banished. Indeed, from this point onward, the appearance of the male nude is rare in Matisse's work, and except for the final Music, 1910, his role is usually the predatory one of the satyr.

Le Luxe I contains many powerful features that had to be sacrificed in order to reach the expressive heights of the final version. Even the barest survival here and there of a brushstroke suggestive of Impressionism indicates the reluctance with which Matisse was shedding many of the received and learned techniques of his youth. The penumbras surrounding the figures, seen earlier, are virtually gone in the sketch, save for the back of the flower girl, and do not appear at all in the final version. And his most brilliant color concept, the pale copper-oxide blue green of the kneeling figure, had to be ruthlessly omitted from the final version for it to attain its unique serenity. In effect, Matisse here gives us a modern Aphrodite risen from the sea, erotic yet narcissistic, destined only for the eyes, attentions, and supplications of her own sex. It is a developed and expanded fragment of Joy of Life, just as, three years later, Dance was destined to be. In Le Luxe the artist offers us more than a hint of his consummate skill as a monumental draftsman, in close conjunction with his adroitly controlled genius in contrasting colors for a maximum of expressive and poetic effect. The stylized arabesques of the figures in Le Luxe and their fluent, graceful, almost lifesize contours map the direction of Matisse's immediate future and point the way to his decorative, architecturally scaled works of the 1930s and later.