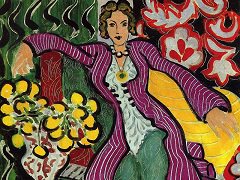

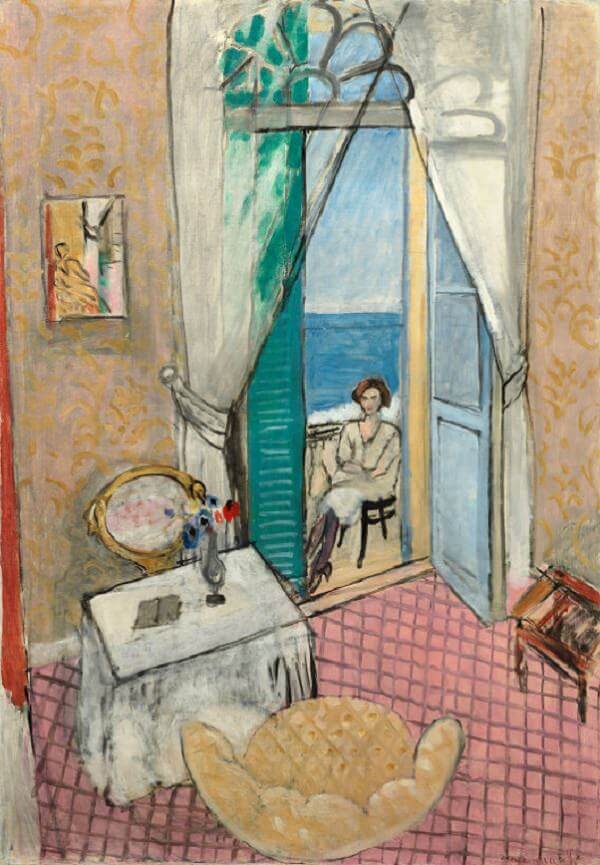

Interior at Nice, 1921 by Henri Matisse

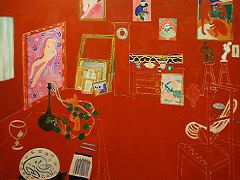

To judge from the color and grid of the carpet, this picture was painted in the same hotel in Nice as was The Artist and His Model. The format and vantage point have been changed, but the soft interior tone and light seem virtually the same. The abrupt, disconcerting changes we can see between L'Atelier Rouge and The Pink Studio a decade previously - both having been painted in the same interior - are here absent, and the temptation is to think that Matisse has allowed his imagination to slacken somewhat. In fact, however, he has simply become more subtle in the varying ways in which he converts a familiar space into a unique pictorial event. The window, now open, returns us to the dichotomy between inner and outer space (one must never forget that a perception of the tensions of inside and outside were a central concern of the major Cubist masters). The model, now clothed, is outside on the terrace, beyond the immediate world of the artist, and hence the picture lacks the closed-in, intimate quality of The Artist and His Model. Furthermore, from the variations in furnishings and of the paintings on the wall adjacent to the window, we perceive a passage of time, a phenomenon significantly lacking in the earlier related studio pictures.

In the present picture, the perspective contradiction offers a provocative intellectual challenge, even though we may be familiar with similar devices in French painting from the time of Vincent van Gogh and Paul Cezanne. We look directly down upon the cushion of the chair in front of the mirrored table while simultaneously looking directly out the window, addressing the eye level of the model. Such contradictions in the spectator's point of view had, of course, been more drastically exploited by the Cubists. Quite obviously Matisse had no such idea in mind when he painted this particular dialogue between interior and exterior space, yet it is remarkable that he was able to integrate this basic theme of recent Western art, which contradicts to one degree or another the fundamental Renaissance laws of linear and aerial perspective, with an atmosphere of sensuality and softness of touch reminiscent of Boucher or Chardin.

In the end we may agree that these two pictures fail to stimulate our attention through dramatic shock, as is the case with Red Studio and Pink Studio, but as imaginary pendants they reveal a degree of refinement and sensibility, a necessary and inevitable progression beyond the earlier stage of events, that shows Matisse's art still in full growth and continued maturation. The very discretion and restraint of their differences in the end piques our curiosity even more profoundly, at least upon reflection. Even more important, these "studios" are populated with actual figures: frequently the artist, almost invariably the model. The theme for his greatest series of drawings of the late twenties and early thirties is here proclaimed. Of his contemporaries, only Pablo Picasso would choose to explore this theme so profoundly, though with radically different psychology.