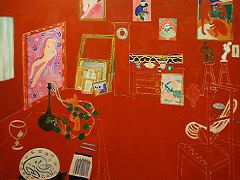

Still Life with Apples on Pink Cloth, 1925 by Henri Matisse

Matisse's first painting, in 1890, was a still life (Books and Candle), and the theme ran through most of his career, frequently finding itself integrated into the larger interior studio pictures, notably Still Life with Aubergines and Interior with Phonograph. Its ultimate metamorphosis would come in the grand Snail. However, the painting of rather classical still life frequently enjoyed an existence of its own as a separate genre in his work. This radiantly beautiful study of yellow apples set against a pink cloth which reverberates with the blue of the background hanging is an exceptionally fine instance of the artist in mid-career, halfway between his beginnings and his culmination. Like many of the odalisques of this decade, this is a pivotal work both in style and subject; like the figure and interior studies, this painting shows the artist seeking an intimacy of scale and a compensatory reduction in overpowering architectonic design. The immediate sensuality of the image, the caress of the touch, are in contrast to pictures that come before and after. And yet this stage in Matisse's development is not inconsistent with the unity and the unfolding of his career. Here he seems to be reinvestigating some of the preoccupations of his youth, especially with respect to the Cezanne's disposition of the cloth and the way in which the fruit and pitcher are inserted into this arbitrary topography.

Interestingly, there are few precedents for exactly this type of composition, with the angle of the table clearly facing the picture plane. Matisse's earlier still lifes, with the exception of the monumental Desserte (1897), tended toward frontality. Clearly, at this juncture in his career he was seeking a new confrontation with the problem of constructing space in depth, using diverging lines of perspective rather than decorative framing devices and changes of scale. As for the resonant color harmonies, they grow from his long preoccupation with this problem. Here they are used to model forms rather than to create pictorial surface tensions. To a degree this preoccupation is contradictory to his goals as a Fauve and to the decorative, planar tendencies of his final works. But the investigations conducted in pictures of this type were a basic catalyst in the historical chemistry of Matisse's art; their role was to refine his sensibility and his proven accomplishments on a near-architectural scale.